This chapter is primarily intended for those readers who are unfamiliar with bar chart construction. We’ll begin by discussing the different types of charts available and then turn our focus to the most commonly used chart-the daily bar chart. We’ll look at how the price data is read and plotted on the chart. Volume and open interest are also included in addition to price.

We’ll then look at other variations of the bar chart, including longer-range weekly and monthly charts. Once that has been completed, we’ll be ready to start looking at some of the analytical tools applied to that chart in the following chapter.

Those readers already familiar with the charts themselves might find this chapter too basic. Feel free to move on to the next chapter.

Chart construction: types of charts available

The daily bar chart has already been acknowledged as the most widely used type of chart in technical analysis. There are, however, other types of charts also used by technicians, such as line charts, point, and figure charts, and more recently, candlesticks.

It’s called a bar chart because each day’s range is represented by a vertical bar. The bar chart shows the open, high, low, and closing prices. The tic to the right of the vertical bar is the closing price. The opening price is the tic to the left of the bar.

In the line chart, only the closing price is plotted for each successive day. Many chartists believe that because the closing price is the most critical price of the trading day, a line (or close-only) chart is a more valid measure of price activity.

Notice here that the point and figure chart shows the same price action but in a more compressed format. Notice the alternating column of x’s and o’s.

The x columns show rising prices and the o columns, declining prices. Buy and sell signals are more precise and easier to spot on the point and figure chart than on the bar chart. This type of chart also has a lot more flexibility. covers point and figure charts.

CANDLESTICKS

Candlestick charts are the Japanese version of bar charting and have become very popular in recent years among Western chartists. The Japanese candlestick records the same four prices as the traditional bar chart-the open, the close, the high, and the low.

The visual presentation differs, however. On the candlestick chart, a thin line (called the shadow) shows the day’s price range from the high to the low. A wider portion of the bar (called the real body) measures the distance between the open and the close. If the close is higher than the open, the real body is white (positive).

If the close is lower than the open, the real body is black (negative).

The key to candlestick charts is the relationship between the open and the close. Possibly because of the growing popularity of candlesticks, western chartists now pay a lot more attention to the opening tic on their bar charts.

You can do everything with a candlestick chart that you can do with a bar chart. In other words, all the technical tools and indicators we’ll be showing you for the bar chart can also be used on candlesticks.

We’ll show you a bit later in the chapter how to construct bar charts for weekly

and monthly periods. You can do the same with candlesticks. “Japanese Candlesticks,” provides a more thorough explanation of candlestick charting.

ARITHMETIC VERSUS LOGARITHMIC SCALE

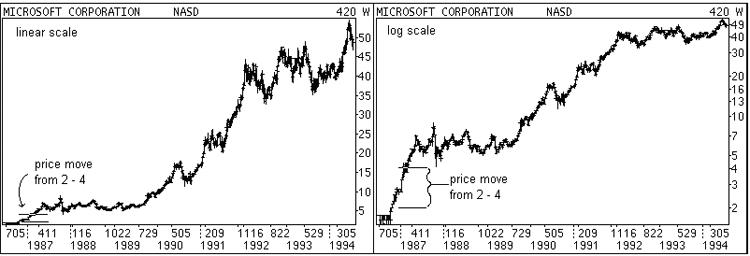

Charts can be plotted using arithmetic or logarithmic price scales. For some types of analysis, particularly for very long-range trend analysis, there may be some advantages to using logarithmic charts.

On the arithmetic scale, the vertical price scale shows an equal distance for each price unit of change. Notice in this example that each point on the arithmetic scale is equidistant. On the log scale, however, note that the percentage of the dis increases gets smaller as the price scale increases.

The distance from points 1 to 2 is the same as the distance from points 5 to 10 because they both represent the same dou. bling in price. For example, a move from 5 to 10 on an arithmetic scale would be the same distance as a move from 50 to 55, even though the former represents a doubling in price, while the latter is a price increase of only 10%.

Prices plotted on ratio or log scales show equal distances for similar percentage moves For example, a move from 10 to 20 (a 100% increase) would be the same distance on a log chart as a move from 20 to 40 or 40 to 80.

Many stock market chart services use log charts, whereas futures chart services use arithmetic. Charting software packages allow both types of scaling

CONSTRUCTION OF THE DAILY BAR CHART

The construction of the daily bar chart is extremely simple. The bar chart is both a price and a time chart. The vertical axis (the axis) shows a scale representing the price of the contract.

The horizontal axis (the x-axis) records the passage of time. Dates are marked along the bottom of the chart. All the user has to do is plot a vertical bar on the appropriate day from the day’s high to the day’s low (called the range). Place a horizontal tic to the right of the vertical bar identifying the daily closing price.

The reason for placing the tic to the right of the bar is to distinguish it from the opening price, which chartists record to the left of the bar. Once that day’s activity has been plotted, the user moves one day to the right to plot the next day’s action. Most chart services use five-day weeks.

Weekends are not shown on the chart. Whenever an exchange is closed during the trading week, that day’s space is left blank. The bars along the bottom of the chart measure volume.

VOLUME

Another piece of important information should be included in the bar chart volume. Volume represents the total amount of trading activity in that market for that day.

It is the total number of futures contracts traded during the day or the number of common stock shares that change hands on a given day in the stock market. The volume is recorded by a vertical bar at the bottom of the chart under that day’s price bar. A higher volume bar means

The volume was heavier for that day. A smaller bar represents a lighter volume. A vertical scale along the bottom of the chart is provided to help plot the data.

- Best Chart Construction Notes: Technical analysis of financial markets John Murphy

- Dow Theory of Technical Analysis, Basic 6 tenets, closing prices, stock market indicator & trade Notes

FUTURES OPEN INTEREST

Open interest is the total number of outstanding futures contracts that are held by market participants at the end of the day. Open interest is the number of outstanding contracts held by the longs or the shorts, not the total of both.

Remember, because we’re dealing with futures contracts, for every long there must also be a short. Therefore, we only have to know the totals on one side. Open interest is marked on the chart with a solid line along the bottom, usually just above the volume but below the price.

Total Versus Individual Volume and Open Interest Numbers in Futures chart services, along with most futures technicians, use only the total volume and open interest figures.

Although figures are available for each individual delivery month, the total figures for each commodity market are the ones that are used for forecasting purposes. There is a good reason for this.

In the early stages of a futures contract’s life, volume and open interest are usually quite small. The figures build up as the contract reaches maturity. In the last couple of months before expiration, however, the numbers begin to drop again. Obviously, traders have to liquidate open positions as the con open tract approaches expiration.

Therefore, the increase in the numbers in the first few months of life and the decline near the end of trading have nothing to do with market direction and are just a function of the limited life feature of a commodity futures contract.

To provide the necessary continuity in volume and Interest numbers, and to give them forecasting value, the total numbers are generally used. (Stock charts plot total volume fig. sure, but do not include open interest.)

Volume and Open Interest Reported a Day Late in Futures

Futures volume and open interest numbers are reported a day late. Therefore, the chartist must be content with a day’s lag in obtaining and interpreting the figures. The numbers are usual.

reported during the following day’s trading hours, but too late for publication in the day’s financial newspapers. Estimated volume figures are available, however, after the markets close and are included in the following morning’s paper.

Estimated volume numbers are just that, but they do at least give the futures technician some idea of whether the trading activity was heavier or lighter the previous day. In the morning paper, therefore, what the reader gets is the last day’s future prices along with an estimated volume figure.

Official volume and open interest numbers, however, are given for the day before. Stock chartists don’t have that problem. Volume totals for stocks are immediately available.

The individual open interest numbers in futures do provide valuable information. They tell us which contracts are the most liquid for trading purposes. As a general rule, trading activity should be limited to those delivery months with the highest open interest. Months with low open interest numbers should be avoided. As the term implies, higher open interest means that there is more interest in certain delivery months.

WEEKLY AND MONTHLY BAR CHARTS

We’ve focused so far on the daily bar chart. However, be aware that a bar chart can be constructed for any time period. The intra-day bar chart measures the high, low, and last prices for periods as short as five minutes.

The average daily bar chart covers from six to nine months of price action. For longer-range trend analysis, however, weekly and monthly bar charts must be used. the method of constructing and updating the charts is essentially the same.

On the weekly chart, one bar represents the price activity for the entire week. On the monthly chart, each bar shows the entire month’s price action.

Obviously, weekly and monthly charts compress the price action to allow for much longer-range trend analysis. A weekly chart can go back as much as five years and a monthly chart up to 20 years. It’s a simple technique that helps the chartist study the markets from a longer-range perspective valuable perspective that is often lost by relying solely on daily charts.

CONCLUSION

Now that we know how to plot a bar chart, and having introduced the three basic sources of information, volume, and open interest’re ready to look at how that data is interpreted. Remember that the chart only records the data. In itself, it has lit-Chart Construction value. It’s much like a paintbrush and canvas.

By themselves, they have no value. In the hands of a talented artist, however, they can help create beautiful images. Perhaps an even better comparison is a scalpel. In the hands of a gifted surgeon, it can help save lives. In the hands of most of us, however, a scalpel is not only useless but might even be dangerous.

A chart can become an extremely useful tool in the art or skill of market forecasting once the rules are understood. Let’s begin the process. In the next chapter, we’ll look at some of the basic concepts of trends and what I consider to be the building blocks of chart analysis.